Data Compression (Ch 7)¶

Huffman Tutorial

This expands on the Shortest Symbol trick from Nine Algorithms and introduces a concrete algorithm for coming up with a shortest symbol code called Huffman encoding.

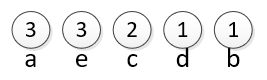

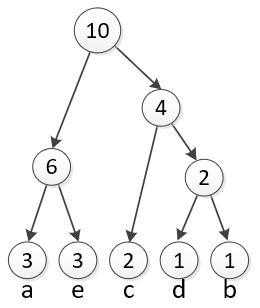

We want to compress messages that only consist of the characters: a, b, c, d, and e. They are used in the proportions: 3 a’s, 1 b, 2 c’s, 1 d and 3 e’s. First, write them down in order from most common to least common. |

|

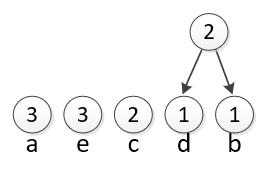

We take the least common pair and join them. The new circle has a value of 2 because it represents the combined d and b (1 of each). |

|

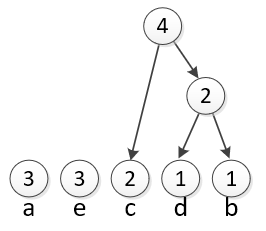

Now we do it again to join the smallest two ungrouped circles together. The new circle has a 4 because it represents 2 c’s, and the group of 2 d’s and b’s. |

|

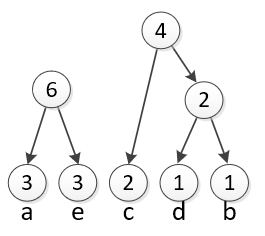

Again, join the smallest two remaining circles. The two smallest circles are the a and e (3 instances of each). So we will join them into a group of 6. |

|

Finally, we can merge the two remaining circles into one final circle. Once we are left with just one group, we are ready to make the code. |

|

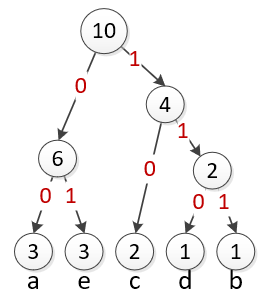

Think of each circle as choosing between two branches. Put a 0 on the left branch and a 1 on the right. |

|

The full table of codes is shown in the table below. Note that the process of building the code resulted in two important features: 1) The most common symbols have the shortest codes. 2) No code is a prefix of another code.

a |

00 |

e |

01 |

c |

10 |

d |

110 |

b |

111 |

Using the code, the sequence aabcea is encoded as “00 00 111 10 01 00”. But because of the way we designed the code, we don’t even need the spaces. We could decode “0000111100100” by working our way from left to right. as shown below:

Code |

Decoded |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

0000111100100 |

Start |

|

0000111100100 |

Is 0 a code? No, continue… |

|

0000111100100 |

a |

Is 00 a code? Yes, it represents a. We have used up the 00. |

0000111100100 |

a |

Is 0 a code? No, continue… |

0000111100100 |

aa |

Is 00 a code? Yes, it is another a. We have used up that 00. |

0000111100100 |

aa |

Is 1 a code? No, continue… |

0000111100100 |

aa |

Is 11 a code? No, continue… |

0000111100100 |

aab |

Is 111 a code? Yes, it represents b. We have used up the 111. |

0000111100100 |

aab |

Is 1 a code? No, continue… |

0000111100100 |

aabc |

Is 10 a code? Yes, it represents c. We have used up the 10. |

0000111100100 |

aabc |

Is 0 a code? No, continue… |

0000111100100 |

aabce |

Is 01 a code? Yes, it represents e. We have used up the 01. |

0000111100100 |

aabce |

Is 0 a code? No, continue… |

0000111100100 |

aabcea |

Is 00 a code? Yes, it represents a. We have used up the 00. |

0000111100100 |

aabcea |

We have consumed all the bits, the message was aabcea |

Optional: Related Readings

Here are three articles related to data compression you might find interesting:

Curious about what kind of algorithm can do the “Same as Earlier” trick (especially on complex patterns)? Check out this page about LZW compression.

How JPEG compression works. Demonstrates how JPEG image compression really works. The full details of the math might be a bit daunting, but interesting to at least skim through.

Compressing a Voxel World. Interesting discussion of someone exploring run length encoding and other techniques for compressing the data in a Minecraft like program.