11.1. Computability¶

Before the first modern computer was even built, Alan Turing had proven that there are some problems that are unsolvable with any conceivable mechanical calculation device - these functions are said to be uncomputable as opposed to computable problems that can be solved by an algorithm in some finite number of steps.

Note

Chapter 10 of Nine Algorithms that Changed the Future describes the basic idea of the proof.

But even in the realm of functions that are theoretically computable, there are problems that are so complex to solve via computation that they are practically uncomputable. We may be able to solve simple versions of the problem, but as the input size grows, the time it takes to find a solution grows so fast that it rapidly becomes unusable.

Problems that have this characteristic are described as non-polynomial problems. This is a way of saying that the Big-O function that governs their behavior is something that can not be written as a polynomial (a function where every term consists of a constant power of n). Instead, the Big-O is something like \(O(2^n)\) where n is the exponent or \(O(n! \times)\) (n! = 1 × 2 × 3 × … × n). The relative growth of some polynomial functions (\(n\) and \(n^2\)) and non-polynomial ones (\(2^n\) and \(n!\)) can be seen below.

\(n\) |

\(n^2\) |

\(2^n\) |

\(n!\) |

|---|---|---|---|

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

10 |

100 |

1,024 |

3,628,800 |

100 |

10,000 |

1.27 x \({10}^{30}\) |

9.33 x \({10}^{157}\) |

If we are solving a problem with a list of 100 items, a \(O(n^2)\) algorithm like Insertion Sort is doable. ~10,000 units of work will take a fraction of a second for a computer to process. On the other hand, assuming the computer can do 10 billion units of work per second, solving a problem using an algorithm that is \(O(n!)\) will take ~4,000,000,000,000 years - you probably will not have the patience to wait around to find out the answer.

So what kinds of problems are non-polynomial? Many very practical problems have no known polynomial time algorithm. Prime Factorization is one example - there is no known algorithm for standard computers for taking a large number and finding its prime factors in polynomial time. Much of modern cryptography and web security is based on the fact that this particular problem is so hard to solve. Should a polynomial time algorithm be found, codes that are considered uncrackable would become easy to defeat. This is one of the reasons for interest in quantum computing… there are quantum prime factorization algorithms that run in polynomial time.

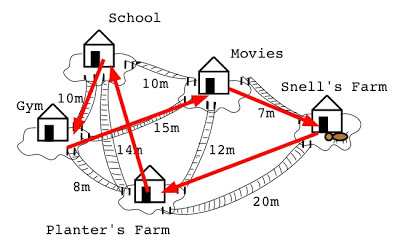

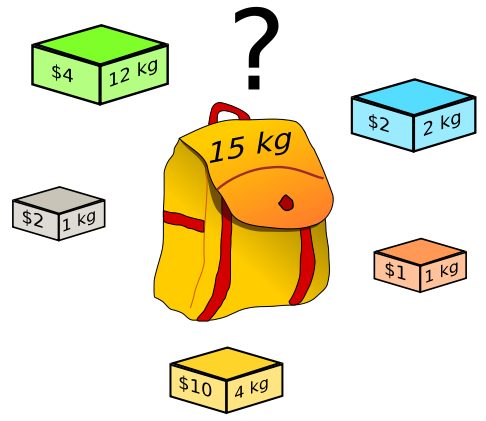

Many optimization problems are also non-polynomial. The traveling salesman problem is to find the most efficient route to visit every city on a map. The brute force approach to solving this problem (try every possible route) is \(O(n!)\). The knapsack problem involves selecting the best subset of items from a list to maximize the value of items placed into a backpack with a limited capacity - it too has no polynomial time solution. Both of these problems relate closely to all kinds of optimization problems we would like to use computers to solve.

Image by Jeremy Kubica

Creative Commons CC BY SA 3.0¶

Traveling Salesman: Is this the best possible route?

Image via Wikipedia Commons

Creative Commons CC BY SA 3.0¶

Knapsack Problem: What collection of items is optimal?

Faced with a problem that is non-polynomial, instead of looking for a perfect answer that will take too long to find, we must instead do things like try to develop algorithms that look for a “pretty good” answer in a tractable amount of time or that can efficiently solve some special subset of the hard problems.

This video does an amazing job of explaining the relationship between polynomial functions (the class known as P) and those problems that we believe to be fundamentally harder. It goes into more detail than we are worried about learning for this class, so do not worry about absorbing every detail. Instead, focus on the explanations of how polynomial functions are different, why Moore’s Law can’t help us with harder problems, and what this all means: