2.5. Loading & Storing¶

ARM is a load/store architecture, meaning that most of the instructions can only work on registers. To work with data we must first load it into a register. When we are done working on it, we store it back to memory.

To load data we use the load register instruction. It typically is a two step process. First we load the address of the data that we want, then we load the data itself. We need this two step process because the memory address we want to load from is a 32-bit value - it cannot be included inside the instruction as it is too big. The address must be loaded into a register that can hold the full 32 bit value.

LDRrd, =LABELLoad rd with the address that corresponds to the thing labeled with LABEL. This gets the address of the data, not the data itself. Similar to the & operator in C/C++

LDRrd, [rn]Load rd with the word of memory at the location stored in rn. This loads the actual data pointed at by the register. This is similar to the * operator in C/C++

.data

x: .word 0x12345678

.text

LDR r1, =x @r1 <- address of x

@int* r1 = &x; in c++

LDR r2, [r1] @r2 <- value at address stored in r1

@int r2 = *r1; in C++

end: b end @stop program

Note

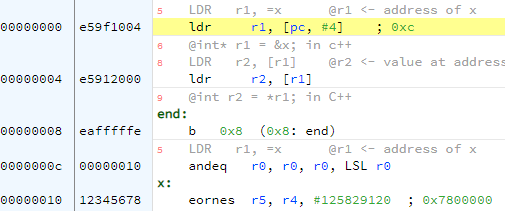

If you look closely at the assembled version of that code, you will notice that in the assembled version, the =x has been replaced

by [pc, #4].

[pc, #4] means 4 bytes past where the Program Counter currently is. When the first LDR runs, the program counter will be 00000000

(the address of that instruction). In early version of the ARM architecture, the PC would actually be 8 bytes past that when the instruction

executed. So the final address would be 0x00000000 + 4 + 8 = 12 = 0xC. If you look at address 0000000C, it contains the data 0x00000010.

0x00000010 is in fact the address of x. The assembler has: 1) calculated the address of x; 2) stored that value in memory at the end of

the .text; 3) set the first LDR to load that value. That is all fairly complex, but most of the time, we do not have to worry about the

mechanics. We just use LDR rd, =LABEL and count on the assembler to manage the details.

2.5.1. Loading an Immediate¶

We can use the assembler’s tricks to have it load a value that is too large/complex to fit as the immediate value in a MOV instruction. A load can specify a numeric value to load, the assembler will place it into memory and automatically calculate the address for it.

LDRrd, =valueLoad rd with the value specified. The value is not an immediate - it does not get # in front of it.

LDR r1, =0xABCDABCD

LDR r2, =45000

end: b end @stop program

Note

A load instruction may be less efficient than MOV instructions that do not rely on a trip to memory. ARMv7 provides MOVT and MOVW

instruction that each can move a 16-bit chunk of data into a register. MOVW loads the lower 16-bits of a register and wipes out the top 16-bits.

MOVT places 16-bits in the top 16-bits of the register, leaving the lower 16 bits unmodified. So a MOVW followed by a MOVT is

likely a more efficient way to load a 32-bit value than loading it.

2.5.2. Storing¶

To store a piece of data back to memory after working on it in registers, we use the store register instruction:

STRrs, [rn]Take the value that is stored in rs and store it into memory at the location in rn. Note that the destination is the second register!!!

The store register instruction needs to have the address it will store to loaded into a register, so it will usually be preceded by a

LDR rn, =identifier instruction that loads the memory address we are going to store to. This program loads data from a variable

x, multiplies it by 2 and stores the answer back to y:

.data

x: .word 5

y: .word 0

.text

_start:

LDR r1, =x @r1 <- address of x (&x)

LDR r2, [r1] @r2 <- x

LSL r2, r2, #1 @r2 <- r2 * 2

LDR r3, =y @r3 <- address of y (&y)

STR r2, [r3] @store from r2 to location given by r3

@y <- r2

end: b end @stop program